I actually had the the opportunity to experience in person

the temporary exhibition The Run-On of

Time of the American photographer Eugene Richards in the Nelson-Atkins Museum

of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. This exhibit covers his career as a photojournalist and documentary photographer

from 1968 to the present, the collection includes 146 photographs, 15

books, and selected videos. After refusing the draft of the Vietnam War,

graduating from Northeastern University, learning large-format photography

alongside Minor White at MIT and later working as a health care advocate in

rural Arkansas, Richards finally returned to Dorchester and began to document

the changing, racially diverse neighborhood where he was born. Over the past fifty

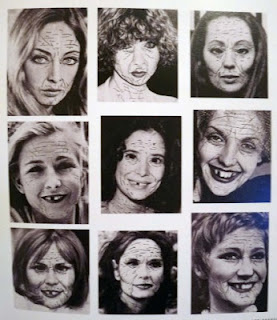

years his oeuvre has consisted of very complicated and controversial topics

such as poverty, emergency medicine, drug addiction, cancer, mental illness,

the impact of war on veterans and their families, caring for the elderly, and

the depopulation of rural America.

In an interview with James

Estrin about this current exhibit, Eugene Richards confessed to the fact the he

never thought of his work as a whole to be as rough as it really is, “I’ve

lived this life, met these people”. He was never trying to just capture the bad

aspects of these neighborhoods, rather he was attempting to reveal something

true about their lives and their humanity. Although at times, one may believe

that we are at lowest lows, but even then, there is still joy and the good

times in which we should not overlook regardless of how simple that one moment

is. In Grandmother, Brooklyn, New York, Richards illustrates to the

audience those wonderful moments of life.

Furthermore, just like Anthony Francis (whom we had at UTSA as a visiting

artist), Richards is very conscious of what it means to go into someone’s

house, into their privacy, and capture those very personal moments in pictures

as we can see in Sgt. Jose Pequeño with his mother, Nelida

Bagley. West Roxbury, Mass and in Crack

Annie, New York City. Ultimately, Richards’s life work illuminate personal

struggles that might otherwise go unnoticed on the day-to-day, with the hope

that his art might spark conversations on how we should care for one another as

human beings.

|

| Grandmother, Brooklyn, New York, 1993 Gelatin silver print |

|

| Sgt. Jose Pequeño with his mother, Nelida Bagley. West Roxbury, Mass2008 Gelatin silver print |

|

| Crack Annie, New York City 1988 Gelatin silver print |